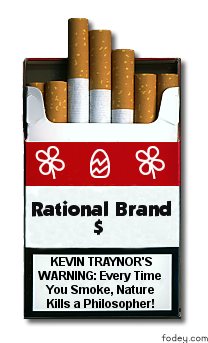

"The commercial morality of the world seems to have been markedly lowered as a result of the war," said one underwriter today, when asked for an explanation of the situation. "The demand for bottoms after the armistice raised shipping to unprecedented values. Insurance valuations increased correspondingly. Then the slump came and values were lowered and owners faced tremendous losses, but insurance policies continued at an artificially high mark. What we term 'moral risk' naturally increased and sinkings began. That is our notion how it all came about." ("Suggests Storms Sank Lost Mystery Ships," The New York Times, June 24, 1921.)

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

General Morne

General Morne, October 19, 1920.

The British schooner General Morne sailed from

Lisbon, Portugal, for Newfoundland on October 19, 1920, and vanished. (Spencer,

p. 108.)

The winter of 1920–21 was one of the worst

on record in the North Atlantic. (Winer, Devil's Triangle,

pp. 79.) That, however, is quite irrelevant in this case, as

her course was not even close to the Bermuda Triangle. If you include

the General Morne

among the triangular victims, you have to include every ship that ever vanished

in the North Atlantic. Thus, whether a storm got her or not, the case is solved

for our purposes.

The General Morne was one of a number of ships claimed by the

Bermuda Triangle in late 1920 and early 1921. The record number of vanishing

ships aroused suspicions that Russian reds were hijacking ships and sailing

them to soviet ports. When government investigators realized how severe the

storms had been, investigations ceased.

While most or all of those ships were

probably really storm victims, it is of course not impossible that some ships

were hijacked by communists. A correspondent of The Washington Post

saw several ships with their names painted out in Vladivostok. (Group, p. 36.)

However, I tend to think those may very well have been Russian ships that had

their tsarist names painted out, pending renaming with, uh, "good

socialist/communist" names.

Finally, those ships not sunk by storms may

be victims of insurance fraud.

Labels:

Case File,

Sinkings,

Solved,

Storm Victims,

Vanishings,

Victims

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Albyan

Albyan, October 1, 1920.

The Russian bark Albyan sailed from Norfolk on

October 1, 1920, and vanished in or near the Bermuda Triangle. (Spencer, p.

108.) She was bound for Gothenberg (Gothenburg, Sweden?). ("More Ships

Added to Mystery List," The

New York Times, June 22, 1921.) Simpson calls her the Albyn and asserts that while

she was claimed to be a free Russian ship that refused to recognize the soviet

government, she was in fact a Finnish four-masted bark from Nystad, and indeed

bound for Gothenburg, Sweden. (Simpson, p. 113.)

The winter of 1920–21 was one of the worst

on record in the North Atlantic. (Winer, Devil's Triangle,

p. 79.) From the weather maps: A southern storm passed over the Eastern

Seaboard through October 1, the day the Albyan sailed. It looks like she sailed after the worst

was over in Norfolk, but she may have found that it was worse than expected at

sea. If she made it through the ass end of that one, Horta in the Azores

reported a strong gale (force 9) on October 17.

The Albyan was one of a number of ships claimed by the

Bermuda Triangle in late 1920 and early 1921. The record number of vanishing

ships aroused suspicions that Russian reds were hijacking ships and sailing

them to soviet ports. When government investigators realized how severe the

storms had been, investigations ceased.

While most or all of those ships were

probably really storm victims, it is of course not impossible that some ships

were hijacked by communists. A correspondent of The Washington Post

saw several ships with their names painted out in Vladivostok. (Group, p. 36.)

However, I tend to think those may very well have been Russian ships that had

their tsarist names painted out, pending renaming with, uh, "good

socialist/communist" names.

Finally, those ships not sunk by storms may

be victims of insurance fraud.

"The commercial morality of the world seems to have been markedly lowered as a result of the war," said one underwriter today, when asked for an explanation of the situation. "The demand for bottoms after the armistice raised shipping to unprecedented values. Insurance valuations increased correspondingly. Then the slump came and values were lowered and owners faced tremendous losses, but insurance policies continued at an artificially high mark. What we term 'moral risk' naturally increased and sinkings began. That is our notion how it all came about." ("Suggests Storms Sank Lost Mystery Ships," The New York Times, June 24, 1921.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)